By Johnson Siamachira

Harare, January 30, 2026 (New Ziana) – Kudzai Gwati sweeps her yard in Mbare, a densely populated suburb of Harare, where the pungent smell of sewerage and garbage mingles with the crisp morning air. Lines of rubbish, far more than mere eye-sores, shadow her home as tantalising scents of childhood memories mix with the harsh realities of life in a city struggling under the weight of its own waste. “In Mbare, the garbage and human waste pile up. It’s an everyday struggle,” Gwati says, her eyes narrowing with worry, “Our children play near this mess, and we worry about their health.”

The vibrant capital of Zimbabwe, once dubbed the “Sunshine City,” now bears witness to a pressing waste management crisis. The city generates waste at an alarming rate, but the systems for handling it, overwhelmed and underfunded, seem chronically ill-equipped. From the narrow streets of Mbare to the bustling marketplace of Highfield, residents grapple with the grim reality of overflowing bins, rampant disease, and the insatiable stench of neglect. This struggle echoes through their stories, illuminating the dire state of waste management in Harare and other urban centres across Zimbabwe.

Harare generates an estimated 0.38kg of waste per person per day, resulting in 207,000tonnes of waste annually.

Historically, Harare’s waste management issues stem from a legacy of colonial neglect and systemic underfunding, including insufficient collection vehicles, a lack of proper planning, high waste, and ineffective policies. The Zimbabwean government’s inability to maintain adequate urban renewal infrastructure has culminated in uninhibited dumping and deplorable sanitary conditions. In the poorest suburbs like Highfield, where Florence Samanga resides, the consequences are stark. “We’ve seen an increase in illnesses. Cholera outbreaks are becoming too common. All because waste isn’t collected frequently,” she laments, her voice shaking with concern for her community.

As Gwati and Samanga wrestle with the realities of daily life in their neighbourhoods, the ramifications extend to local businesses as well. Martin Bopoto, a businessman in Mufakose, finds himself in a bind: “My customers often complain about the smell. I had to pay for private waste collection just to keep my business running.” The economic implications of ineffective waste management swirl together with health risks, further entrenching the cycle of poverty and despair.

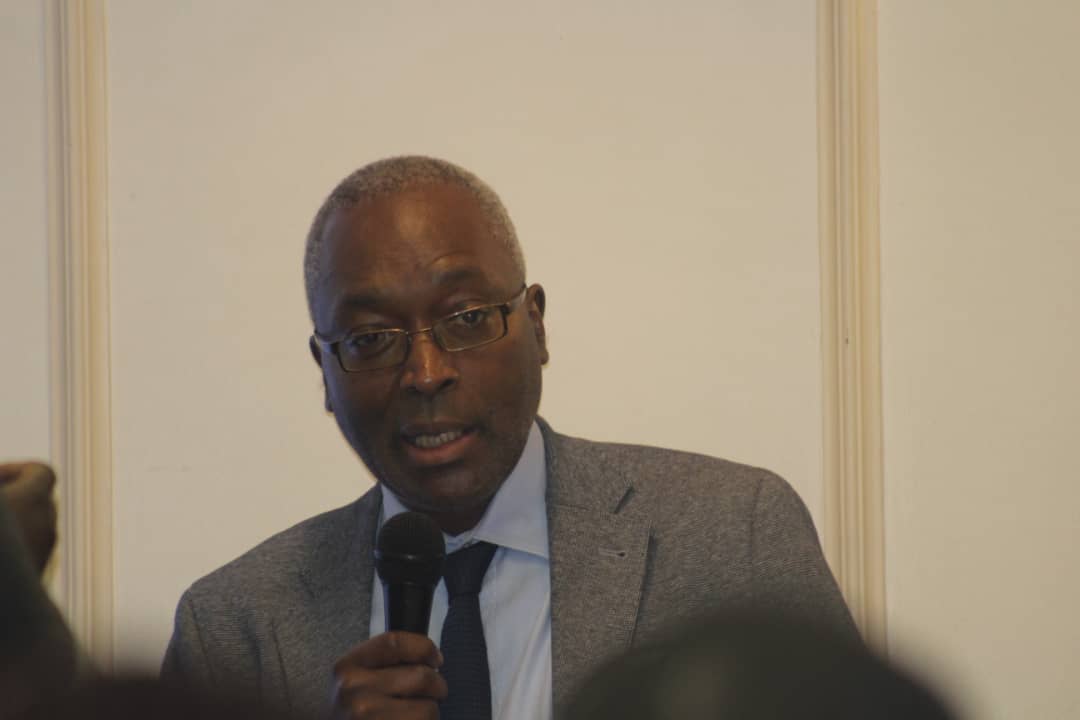

Experts highlight the systemic failures behind these harsh realities. Precious Shumba, director of the Harare Residents Trust, identifies enduring issues rooted in poor governance and inadequate funding. “The root of this problem runs deep. Historical neglect has led to systemic failures in waste management,” he explains, urging for immediate and inclusive reform. “Without proper funding and infrastructure, we’re set to fail.”

Dr. Prosper Chonzi, Harare’s Director of Health, attributes the city’s significant sewage and solid waste management challenges primarily to a lack of resources and underinvestment in infrastructure. He consistently emphasises that poor waste management is the root cause of recurrent waterborne disease outbreaks like cholera and typhoid.

‘’The council often fails to collect refuse regularly due to a shortage of functional vehicles ( only 33 trucks available instead of an estimated 120 needed) and equipment. This leads to the accumulation of uncollected garbage in open spaces and illegal dumping, creating a breeding ground for diseases,’’ he says.

The immediate consequence of poor sanitation and waste management is the prevalence of waterborne diseases. Dr. Chonzi has often noted that instead of focusing on chronic ailments, his department is constantly in “reaction” mode, battling preventable outbreaks of cholera, typhoid, and dysentery.

In response to the mounting crisis, the local authority has recently partnered with Geo Pomona Waste Management. This public-private partnership aims to revitalise the beleaguered waste management system through improved collection services and innovative projects, including a waste-to-energy initiative. However, skepticism remains high. Mayor

Jacob Mafume says, “We acknowledge the challenges. Our plan prioritises an integrated waste management system. But we need community involvement and support.”

The scenes in Harare are visually troubling, and the health implications are dire. Clogged drainage systems lead to severe flooding risks; uncollected waste breeds a cesspool of diseases such as choleral, typhoid, and malaria. The health crisis looms larger by the day, with residents like Gwati caught in its crosshairs. “Without effective waste management, the city’s reputation, economy, and, most importantly, our health are in jeopardy,” she says, voicing her community’s growing frustration.

Yet, within the chaos lies a glimmer of hope. As the government rolls out new strategies aimed at revitalising waste management, the community mobilises for change. New equipment is promised, and clean-up initiatives give residents a chance to engage. But lingering questions echo through crowded streets: Can these new strategies be sustained? How will the council ensure compliance and public involvement, especially in a city where awareness around waste management remains heartbreakingly low?

The challenges Harare faces are multifaceted, but the solutions can be as well. Each resident plays a part in the broader puzzle. As Samanga puts it, “We need to change people’s mindsets regarding waste management. There should be community participation in waste management.”

To reclaim Harare’s former glory as the Sunshine City, collective effort, transparency, and innovative solutions are paramount. The road ahead is fraught with obstacles, yet the vibrant resilience of its people promises a brighter future. With dedication and cooperation, Harare can transform from a ‘Garbage City‘ into a model of sustainability—one clean street at a time. As Gwati sweeps her yard, she envisions a day when her children can play freely, unburdened by the debris of neglect, and a new narrative can emerge from this once-persistent challenge.