By Thabisani Dube

Across Zimbabwe’s rural landscapes, where the roar of lions’ drifts into the rhythm of village life, a quiet innovation is reshaping coexistence. For decades, communities bordering Hwange National Park faced a nightly dilemma: how to protect their cattle from lions without resorting to lethal retaliation.

The solution has emerged in the form of mobile bomas—ingenious portable enclosures that are transforming both conservation and community resilience.

Founded in 2012, the Long Shields Guardian Programme is a conservation initiative working along the boundaries of Hwange National Park. Managed by the Wildlife and Communities Action Trust, the programme combines ecological and social impact. Its monitoring and evaluation are led by WildCRU (Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Oxford University), which also provides opportunities for Zimbabwean students and postdoctoral researchers to analyse data, shaping the programme’s direction and sharing lessons nationally and internationally.

The programme was born out of a pressing conservation context: livestock depredation often led to retaliatory lion killings, contributing to population declines and weakening landscape connectivity. By employing local Guardians, introducing early warning systems, and innovating livestock husbandry through mobile bomas, Long Shields has become a model of coexistence.

Unlike traditional kraals, which require cutting down trees for brushwood and logs, mobile bomas are built from durable PVC material. This innovation reduces pressure on local forests, helping to conserve habitats while still keeping livestock safe. In this way, mobile bomas protect cattle, save lions, and safeguard trees — strengthening both biodiversity and community resilience.

“In Sianyanga, we used to lose cattle every year to lions. Since we started using the mobile bomas, not one has been taken. My family sleeps peacefully now, and our harvests are better because the manure enriches the soil,” says Irvine Ncube a farmer from Sianyanga village, reflecting on the change.

Farmers rotate the bomas across their crop fields, allowing cattle manure to fertilise the soil.

“When we move the boma into the maize field, the soil becomes rich. The harvest is better, and we don’t have to buy as much fertiliser,” explains Kenneth Dube another Sianyanga farmer, who has adopted the system.

This observation is backed by research: WildCRU and Wildlife Conservation Action report a 30 percent increase in crop yields in fields fertilised by mobile bomas.

The Long Shields Guardians—local community members trained and employed through the Wildlife and Communities Action Trust—play a central role in this success. They patrol daily, monitor lion movements via Global Positioning System (GPS) collars, and alert villagers when predators approach. Through a WhatsApp group, Guardians receive live updates when collared lions move out of the park, allowing them to warn farmers instantly and, in some cases, physically deter lions back into protected areas. Their work ensures that mobile bomas are not just structures, but part of a wider system of coexistence.

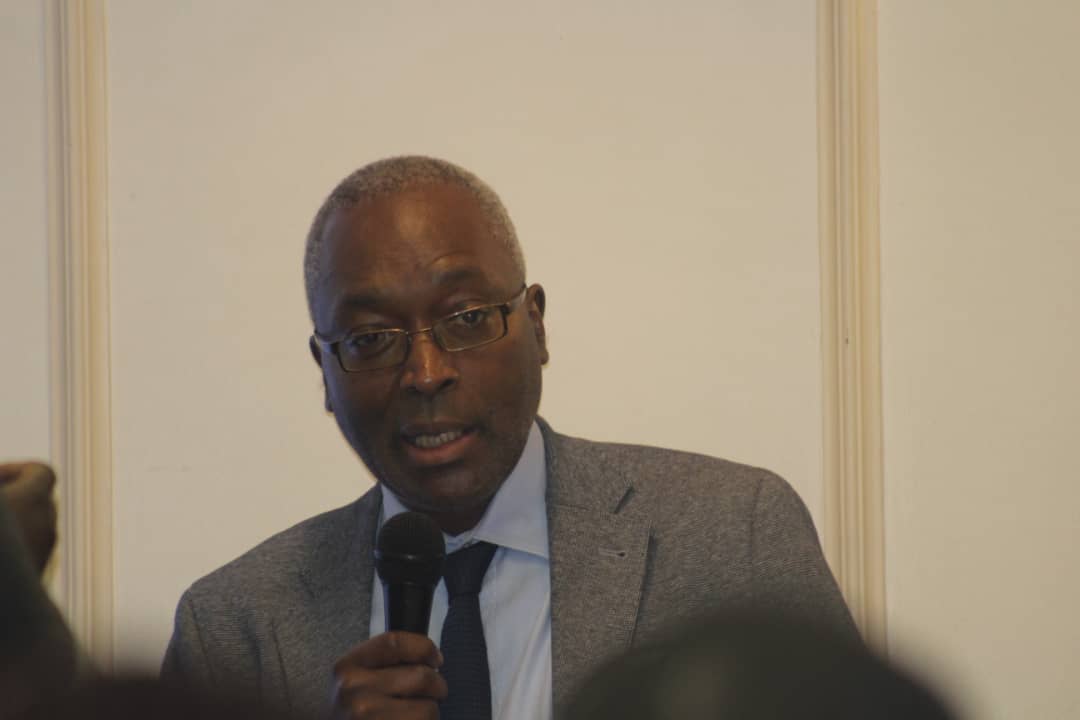

“We are protecting both cattle and lions. If the cattle are safe, people don’t kill lions. That is our mission,” says Mike January, the programme’s manager.

Wildlife Conservation Action, a key partner in Zimbabwe, frames mobile bomas as a breakthrough in community-led conservation.

This sentiment is echoed by the Wildlife and Communities Action Trust, which coordinates the Guardians on the ground, and by WildCRU at Oxford University, which oversees monitoring and evaluation. Together, they highlight the programme as a rare example of a win–win: protecting livelihoods while safeguarding biodiversity.

“Community-led conservation is the only way to secure coexistence. Mobile bomas are not just protecting cattle—they are empowering farmers and saving lions,” says Dr. Moreangels Mbizah, founder and director of Wildlife Conservation Action.

What began in Hwange has inspired interest across Zimbabwe. In Matabeleland, predator‑proof bomas promoted by the Mother Africa Trust are enriching soils while safeguarding livestock, showing how the concept can adapt to different landscapes. Conservation organisations trained in the Long Shields methods are now exploring applications in other regions, including the Zambezi Valley, where human–wildlife conflict is also a pressing challenge.

The ripple effect extends beyond Zimbabwe’s borders. Eighteen conservation organisations from Zimbabwe, Zambia, Namibia, and Botswana have already been trained in these methods, and 10 prides of lions along Hwange’s boundary are closely monitored as potential contributors to conflict. This regional reach positions Zimbabwe as a leader in coexistence innovation and community – based natural resources management, with mobile bomas recognised as a model that can be scaled nationally and shared across southern Africa.

Equally important are the social benefits. The initiative has created employment for 11 Guardians, who patrol communities daily, repair livestock enclosures, and act as vital liaisons between farmers and conservation bodies. It has also opened doors for the next generation of conservationists.

Mobile bomas are more than fences. They are symbols of innovation, resilience, and coexistence. By protecting cattle, they save lions. By fertilising fields, they feed families. And by empowering communities, they show that conservation is strongest when it grows from the ground up. From Hwange to Matabeleland and beyond, Zimbabwe is showing the world that coexistence is not only possible, but powerful.

3

3