By Thabisani Dube

In Zimbabwe, the phrase “man up” encapsulates a cultural expectation that men should suppress their emotions and bear responsibilities without complaint. From homes to workplaces, this stoicism masks a troubling reality: men are dying younger and suffering silently. The crisis is evident in the stark statistics: Zimbabwean men face significant mental health challenges, yet many remain reluctant to seek help.

Globally, men live shorter lives. The World Health Organization estimated male life expectancy at 71 years in 2023, compared to 76 for women. By 2025, similar figures from Worldometer projected 70.9 years for men and 76.2 for women, underscoring a persistent gender gap. In Zimbabwe, factors such as poverty, violence, and a healthcare system that neglects men exacerbate this divide.

At Mpilo Central Hospital in Bulawayo, a troubling internal report from early 2025 revealed 38 male suicide attempts in just two months—more than triple the previous year’s total. In response, the hospital expanded its mental health services. The 2023–24 Demographic and Health Survey estimates Zimbabwe’s suicide rate at 18 deaths per 100,000 people, with men aged 25 to 44 particularly affected. In Bulawayo, police recorded 21 suicide deaths between June and August 2024, with 20 of the victims being men.

These figures reflect a deeper, hidden pain. Clinical psychologist Dr. Olga Filippa Nel, based in Harare, emphasises the stigma surrounding mental health issues, often viewed as signs of weakness or madness. Many men fear judgment and perceive seeking help as incompatible with masculinity. Patriarchal norms demand emotional toughness, forcing men to internalise distress that can manifest as aggression, substance abuse, or physical ailments. Often, they interpret mental health struggles as spiritual attacks, opting for traditional healers over mental health professionals.

In tightly-knit communities, concerns about privacy, limited awareness of mental health, and the high cost of therapy deter men from seeking help. Underfunded mental health services make informal support systems more accessible and familiar.

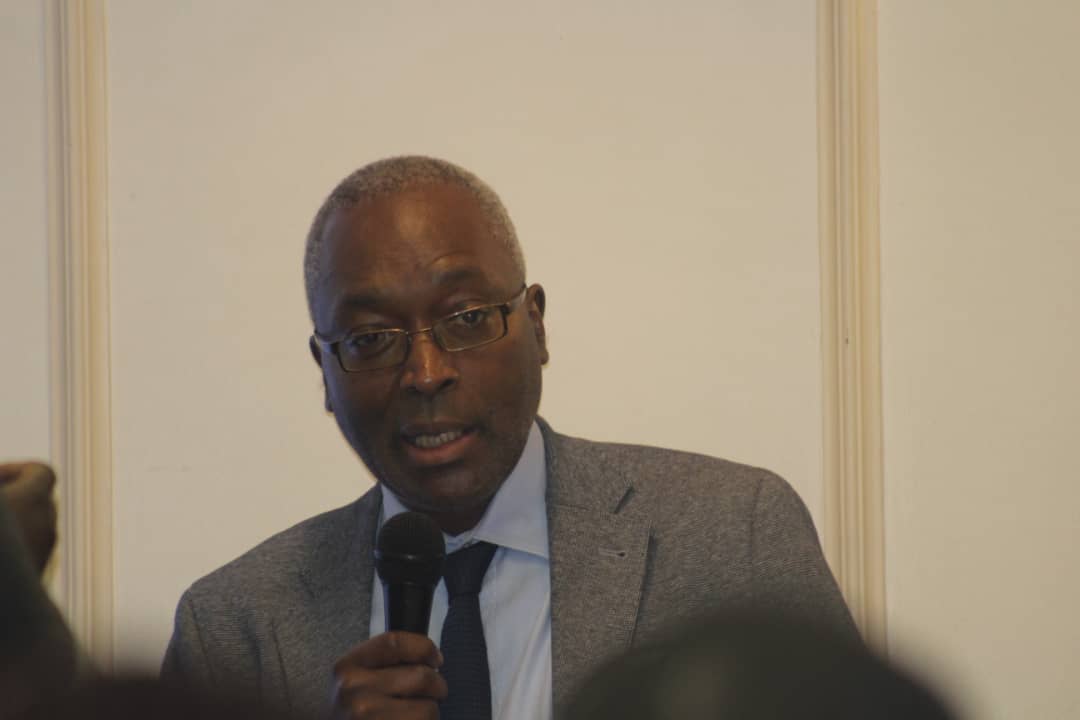

Psychiatrist Dr. Anesu Chinoperekwei asserts that Zimbabwe’s psychiatric services are capable of addressing the rising demand for male mental health support, particularly in public hospitals. However, access remains uneven, especially in rural areas. Dr. Fungai Musinami, Hwange District Medical Officer, stresses the necessity of early intervention and community outreach, advocating for district-level health systems to empower men before their struggles escalate.

Despite alarming data, men’s health remains largely overlooked in Zimbabwe’s national health policies. The Ministry of Health and Child Care has yet to implement a formal programme targeting men’s mental health. Insiders suggest discussions are ongoing, but tangible commitments are lacking. This raises critical questions: why does men’s health remain an afterthought in national strategies? Is it because men are perceived as less vulnerable, or because the stigma surrounding male vulnerability makes it politically convenient to ignore? Until policymakers confront these issues, the crisis will continue to grow.

Faith communities in Zimbabwe play a crucial role in supporting men’s mental health. Pastor Simba Woloza of Fathers Voice Ministries in Ruwa, just outside Harare, encourages churches to promote emotional openness, citing biblical figures like King David as examples of vulnerability. He notes that while women’s ministries flourish, many churches lack dedicated spaces for men. Establishing men’s ministries could help address issues like isolation, substance abuse, and emotional suppression. Some fellowships have begun integrating mental wellness into their programmes, yet broader efforts remain essential.

The crisis is not just theoretical; it’s personal. In August 2025, the suicides of two university students, Abraham Chabata and Takudzwa Mapurisa, shocked the nation. Both had silently battled mental health challenges. Their deaths prompted calls for increased counseling services, yet the stigma persists. One male survivor, choosing to remain anonymous, shared that he once viewed seeking help as a sign of weakness. After connecting with someone, he realised he wasn’t alone. His message to other men is clear: it’s okay to feel, and it’s okay to ask for help.

At the grassroots level, advocates like Lameck Muzangaza of Youth Advocates Zimbabwe work to change the narrative. From childhood, boys learn that vulnerability is a weakness, leading many to internalise pain until it becomes unbearable. Substance abuse, particularly of unregulated brews like “Kambwa,” has become a common escape, fueling domestic violence and even homicide. Muzangaza calls for community dialogues, social media campaigns targeting toxic masculinity, and expanded toll-free helplines to normalise conversations about mental health and influence policymakers.

Dr. Farzana Naeem, chief clinical psychologist and founder of Gateway Mental Health Rehabilitation, highlights systemic barriers that hinder Zimbabwean men from seeking help—stigma, limited awareness, cultural expectations, and fear of social repercussions. Many men worry that opening up could jeopardise their jobs or family relationships, prioritising financial survival over emotional well-being.

“Men are taught to endure, not to express,” she explains. “But psychology is not a luxury; it’s a necessity. It empowers individuals to lead healthier, more fulfilling lives.”

As suicide rates continue to rise, Dr. Naeem emphasises the need for a multifaceted response: public awareness campaigns, stronger community support networks, and improved access to mental health services. Normalising discussions around mental health is crucial to dismantling stigma, allowing men to embrace vulnerability as a strength rather than a flaw.