By Thabisani Dube

Zimbabwe is facing a deepening road safety crisis. From Harare’s busy streets to the winding highways of Masvingo and Nyanga, traffic accidents are claiming lives at an alarming rate. Between January and June 2025, the Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) recorded over 28,000 accidents, with 24 deaths and 170 injuries during the Easter and Independence holidays alone.

Among the most harrowing transport tragedies in recent memory was the August 30 collision on the Mutare–Masvingo highway. A passenger bus attempting to overtake veered into the path of a timber hauler, causing a catastrophic collision. The timber logs pierced through the bus, killing eight passengers instantly and leaving several others critically injured.

“These accidents are largely due to human error—speeding, overtaking misjudgements, and failure to follow traffic laws,” said Commissioner Paul Nyathi, ZRP national spokesperson. His words echo the growing concern across the nation as families mourn and communities demand change.

Just days earlier, on August 28, the nation mourned the tragic loss of Panashe Mwinga, a promising graduate of Chinhoyi University of Technology. Panashe had died in a car crash near Mapinga, along the Harare-Chirundu highway, after celebrating her achievement. Her death prompted the university to declare ‘Black Monday’—a day of mourning that captured the heartbreak of a life cut short.

The most haunting reminder of Zimbabwe’s road safety crisis remains the Nyanga School Bus Disaster of August 3, 1991. A bus carrying 98 students and teachers of the Roman Catholic run Regina Coeli veered off a mountainous road and plunged into a ravine, killing 89 people. Survivors said passengers had begged the driver to slow down. The incident was cited as the worst road accident in the country’s history, caused by brake failure. Decades later, similar risks—poor maintenance, driver error, and weak regulation—still threaten lives.

According to the 2022 Census, about 70 per cent of Zimbabwe’s population lives in rural areas. The Infrastructure Development Programme of 2025 highlights the dire state of rural transport, noting communities rely on aging, poorly maintained vehicles and frequent breakdowns. While rural drunk driving statistics are hard to quantify, anecdotal evidence and community reports suggest reckless, intoxicated driving remains a persistent issue.

On 22 July 2025, a commuter omnibus collided with a haulage truck in Chitungwiza, resulting in 17 fatalities, including the 25-year-old kombi driver.

Behind every statistic are grieving families left to cope with sudden bereavement, funeral costs, and psychological trauma. Hospitals have reported a surge in accident-related admissions, straining limited resources. A general practitioner at a major hospital, speaking anonymously, described the strain: “We’re doing our best, but the lack of resources makes it nearly impossible to manage effectively.”

Dr. Clayton Choga, a family therapist, emphasised the deep psychological toll road traffic accidents can have on survivors: “Survivors often grapple with post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and even survivor’s guilt. These effects can strain relationships, impair cognitive function, and in some cases, lead to substance abuse.”

He also outlined how communities can play a vital role in recovery: “Healing requires community support, awareness, and access to trauma care.”

Kombi drivers, often blamed for reckless behaviour, argue the system itself puts them under pressure. With tight schedules, dilapidated roads and minimal regulation, drivers face daily risks. As one commuter driver stated, “We’re under pressure every day – long hours, tight targets, and roads in bad shape.”

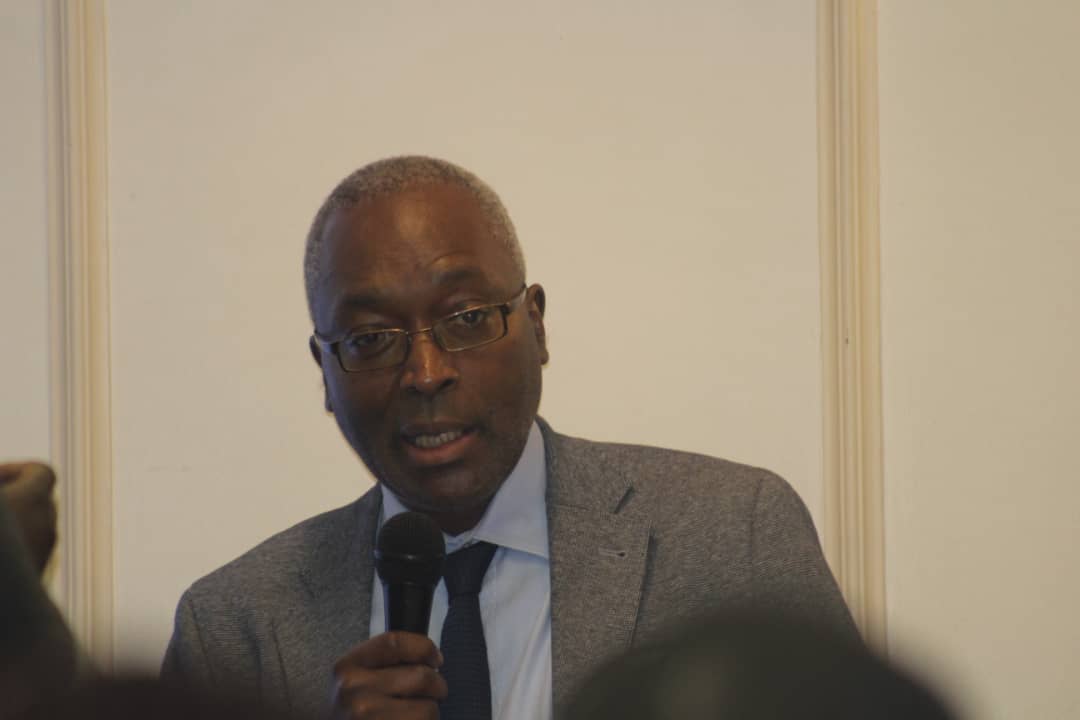

Ngoni Katsvairo, chairman of the Greater Harare Association of Commuter Operators (GHACO), emphasised the need for driver accountability and systemic reform. “About 94 per cent of accidents are caused by human error, and we need to ensure our drivers are well-trained through defensive driving courses.” He added, “Drivers must stop pressuring themselves to meet unrealistic targets and must rest adequately when off duty.”

GHACO is pushing for investment in speed limiters, breathalysers, and drug testing equipment at bus ranks as part of a self-regulation initiative to restore public trust.

Bindstone Katsande, General Secretary of the Zimbabwe Union of Drivers and Conductors (ZUDAC), noted systemic challenges persist despite the union providing medical screenings and defensive driving courses. “We’ve engaged authorities to push for fair wages, but our efforts often hit stumbling blocks,” he said. Katsande called for interventions like speed cameras, humps, and grids at black spots.

Katsande also opposed a new regulation banning drivers under the age of 30 or with less than five years’ experience from operating public vehicles, arguing it could backfire on the national economy. “These youths may be seen as immature, but their age matches today’s working life span,” he said. Katsande concluded by calling for unity and reform to “tame the jungle and reduce accidents on Zimbabwe’s roads.”

In response, the government has introduced new regulations aimed at improving safety and accountability. New regulations now ban drivers under 30 or with less than five years’ experience from operating public service vehicles.

Transport Minister Felix Mhona stated the government’s goal is to ensure accident victims reach nearby hospitals quickly to receive urgent care. Following the Chitungwiza tragedy, the Zimbabwe Catholic Bishops Conference issued a statement calling it a “solemn call to recommit to the sanctity of human life and the urgent need for safer roads.”

Panashe Mwinga’s story has inspired a generation to champion safer travel and responsible driving. Zimbabwe’s roads are now a battleground, and the recent wave of accidents is a national crisis. The road ahead must be paved with responsibility, compassion, and a commitment to life. As the country mourns, it must also mobilise—uniting communities, policymakers, and drivers to build a safer future.