By Thabisani Dube

In the dense forests and rolling hills of Zimbabwe, countless heroes lie beneath unmarked soil, their sacrifices known only to a few. Each year, as the nation commemorates Heroes Day, the stories of celebrated figures like Josiah Tongogara, Jason Ziyapapa Moyo, Nikita Mangena and Herbert Chitepo echo through the air. Yet, for every hero and heroine immortalised in stone, there are many more—nameless and faceless—whose bravery shaped Zimbabwe’s struggle for independence.

As Zimbabweans gather at Heroes Acre to lay wreaths and sing hymns, a deeper narrative unfolds—a narrative of silent sacrifices and forgotten stories that form the bedrock of the nation’s freedom. These untold tales, passed down through whispers and oral traditions, highlight the experiences of guerrillas, messengers, and ordinary citizens who played vital roles in the liberation war.

The liberation struggle, which spanned more than 15 years, resulted in the loss of thousands of lives. While national monuments honour a select few, many remain buried in shallow graves across Mozambique, Zambia, and within Zimbabwe itself. These were the guerrillas who died in ambushes, children who risked their lives as couriers, and women who offered shelter and sustenance to fighters.

In rural Tinde, in Binga district in Matabeleland North Province, Esther Nyathi recalls the hidden history with a clarity sharpened by pain and pride. “History books recount battles and speeches, but they miss the essence of hiding a wounded fighter in the granary,” she says. “We bathed men with bullet wounds and broken hearts. That was courage, too.”

Lucia Mupfuti from Gokwe North remembers a girl of just 14 who carried messages hidden beneath her skirt, crossing the crocodile-infested Sengwa River. “She never made it into any official list,” Lucia says, “but we remember her. Her name lives in us.”

From Bulawayo, Bertha Tshuma, a passionate youth leader, expresses her commitment to preserving these stories. “I’ll engage with elders to learn about their lives and sacrifices, not just battles. Music and drama will help us share these experiences culturally,” she explains. She envisions a digital campaign to link liberation ideals with present-day justice, using platforms like TikTok and Instagram to engage younger generations.

“If we record oral histories now, they can serve as educational tools before they vanish with the older generation,” she adds.

Zimbabwe’s landscape is dotted with undocumented but sacred sites—like the cave in Lupane that sheltered freedom fighters and the riverbank in Mutoko where villagers recall a young boy who drowned delivering a critical message. In Gokwe South, elders recount a maize field where a woman was executed for sheltering guerrillas. Despite their historical significance, these places remain unmarked and unprotected.

“Our soil holds stories no monument has yet marked,” says Sibusisiwe Ncube, a traditional leader in Hwange district, in Matabeleland North Province. “We must safeguard these memories so they do not vanish with the last who remember.”

Chiefs, elders, and spiritual custodians have long kept these histories alive through oral traditions—songs, ceremonies, and storytelling. Yet, as time passes, so do the memories.

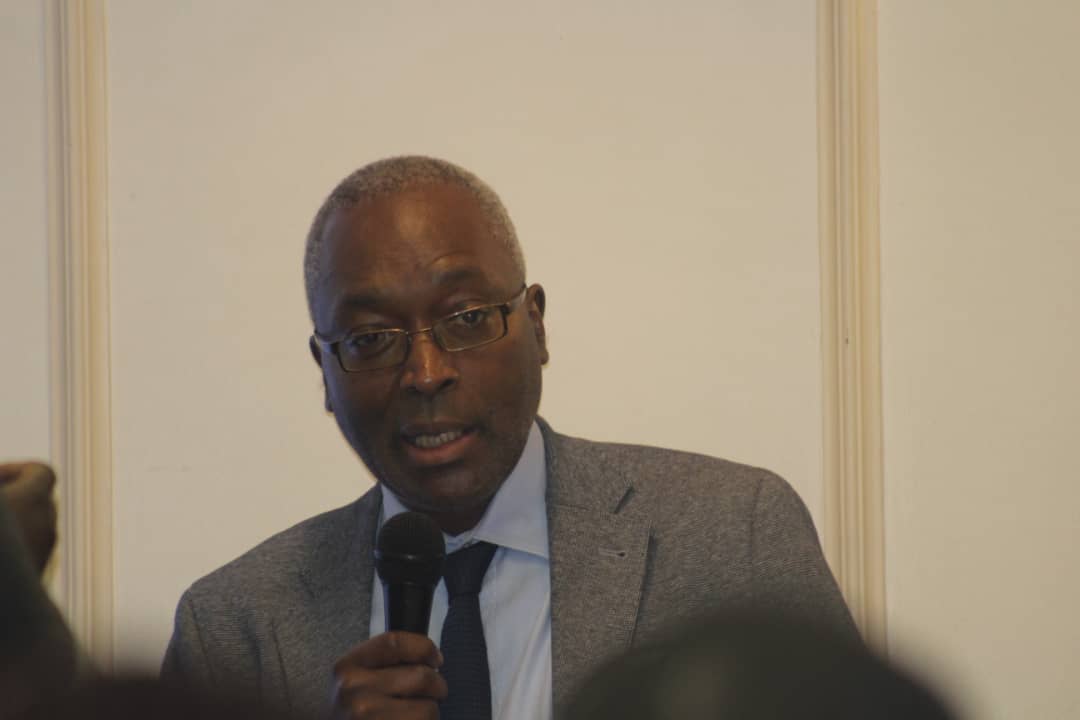

Njabulo Khumalo, Lecturer in Archival Studies, University of Zimbabwe and documentary heritage specialist with experience in the Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA) war archives and oral memory preservation sheds light on the challenges of preserving these narratives. “Having worked with the ZIPRA Trust, we found journals and memorabilia rich in history, yet untouched, locked away in suitcases and shelves,” he explains. “The National Archives has not captured these narratives.”

Khumalo notes that post-independence violence, particularly in Matabeleland and Midlands provinces, has silenced ZIPRA-related stories. “Organisations like Mafela Trust have kept these narratives alive outside the country. For true visibility, journalists and historians must collaborate with grassroots organisations that communities trust.”

The Catholic Church also plays a role in remembrance. Each year on November 2, All Souls’ Day, Catholics pray for all the departed souls, including those unnamed heroes of liberation. “We remember the fighters in our petitions, asking God to receive them,” says Bishop Rudolph Nyandoro of Gweru.

Minister Kazembe Kazembe of the Ministry of Home Affairs and Cultural Heritage says that efforts are underway to memorialise more liberation sites. “We are identifying and documenting places of historical significance,” he told New Ziana. “Sites like Pupu, Kamungoma, Dzepasi, and Butcher have been recognised. Altena Farm is next.”

However, thousands of sites remain unacknowledged by history. This Heroes Day, it is not enough to honour the visible few; we must delve into the silences that conceal stories buried beneath soil and fear.

Let us light candles not only at Heroes Acre but also in our homes, schools, and churches. Let us speak the names we know and record those we do not. By preserving sacred sites and documenting oral histories, we can expand our definition of heroism.

For where courage sleeps, truth awakens. A nation that remembers only part of its past builds a fractured future. “We must build memory where there is none,” Khumalo urges. “Otherwise, we inherit only half a nation.”